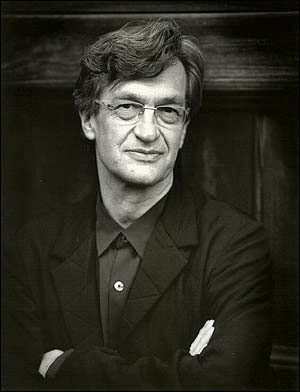

Wim Wenders

Birthday: 14 August 1945, Düsseldorf, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany

Birth Name: Ernst Wilhelm Wenders

Height: 191 cm

Wim Wenders is an Oscar-nominated German filmmaker who was born Ernst Wilhelm Wenders on August 14, 1945 in Düsseldorf, which then was located in the British Occupation Zone of what became the Bundes ...Show More

[on whether he will continue to film in 3-D] I will not do anything else. I'm completely hooked. I t Show more

[on whether he will continue to film in 3-D] I will not do anything else. I'm completely hooked. I think 3-D is a still unexplored cinematographic story. In my books, it's the ideal medium for the documentary of the future. It's not invented to show us different planets. It's invented to show us our own planet. Hide

It is the fate of all culture to be forgotten and to disappear. Sometimes it needs an archaeological Show more

It is the fate of all culture to be forgotten and to disappear. Sometimes it needs an archaeological effort to bring it back to light. I think it's an exciting time to be making movies, to record these changes and sometimes to evoke things that are about to disappear, evoke things we might want to hold on to. Hide

[on the subject of his Oscar-nominated documentary] Pina was a perfectionist in a different way. She Show more

[on the subject of his Oscar-nominated documentary] Pina was a perfectionist in a different way. She wanted each dancer to be completely himself or herself. She didn't want them to play any parts. That was an amazing process to see. To see them do it, not fake it. Hide

I'm one of those guys to whom the saying can be applied, about the prophet in his own country. New G Show more

I'm one of those guys to whom the saying can be applied, about the prophet in his own country. New German Cinema was an invention by the American press-they coined it. Fassbinder, Herzog, myself, and a few other guys. We were looked at like a hopeless bunch of freaks in Germany. Only the recognition we got in America helped us. So I'm extremely grateful for the way my films were received in America. I remember I arrived in New York in January 1972 for the very first time, because MoMA had their first New Directors season, and I was one of the 12 who was going to present his first film here. That was the very first time I gave an interview. The film of mine was received sort of positively, and with respect, and in Germany, we were the outlaws. Nobody knew what to do with us. (...) Because Germans were burned with 15 years of filmmaking under the Nazis, where it was strictly propaganda. After that, throughout the 50s and 60s, German cinema was very much influenced by American cinema. Germans didn't really have confidence in their own stories, or in the fact that cinema could be a reflection of their own history. Thus they looked at American movies, and were happy to not be in any dilemma about their history. When we showed up in the late 60s and early 70s, people were not used to being confronted with themselves. I think the openness with which American audiences and critics received us helped us to be taken seriously. My films, from the beginning, had been heavily influenced by American cinema, so that helped a lot for them to be understood here. [2015] Hide

I've turned from an imagemaker into a storyteller. Only a story can give meaning and a moral to an i Show more

I've turned from an imagemaker into a storyteller. Only a story can give meaning and a moral to an image. Hide

Now, more or less, people take it for granted that movies don't have anything to do with their lives Show more

Now, more or less, people take it for granted that movies don't have anything to do with their lives. That has become the definition of movies. I think that's sad. I think movies can enlighten our lives in a beautiful way, and I have a strong affinity for reality and for what it feels like to be alive today and the whole bloody mystery of life. I think it's something that movies can enlighten. But that idea by now is almost obsolete. [2015] Hide

In a nutshell, Hammett (1982) was shot twice. The first film was shot entirely on location in San Fr Show more

In a nutshell, Hammett (1982) was shot twice. The first film was shot entirely on location in San Francisco only. Not a single second in the studio, everything on location in real places in San Francisco. The studio didn't like it. There wasn't too much action, too much time was dedicated to Hammett the writer and not enough to Hammett the detective. He became a writer out of necessity because he became sick and couldn't work as a detective anymore. He decided to write about his experiences and in that idea "Hammett" was based. So my first shoot was strictly set in San Francisco and really based on the actual character of Hammett. The studio didn't like it, they thought it was too slow and they wanted more of the fantasy and the detective. In the final product ten shots survived from my original shoot: only exteriors. Because there wasn't much money left, and I was too stubborn to drop it and or say, "Well then let somebody else do it." Francis Ford Coppola was too stubborn to fire me so we stuck it out and we respected each other in spite of all the conflicts. So I ended up shooting the second version as well. That was entirely in one sound stage. The whole [first] shoot never saw the light of day, except for a couple of shots from the first, maybe 5% of the film from the first version. (...) [The first version] was destroyed. It doesn't exist now. They only kept a cut negative, everything else is junked. Which I found out really late and I don't know who was to blame. I don't know. Anyway, I was very disappointed. At one point I suggested to Zoetrope that I could finish [that version] and wouldn't it be an interesting case study to present the two films? They said, "Oh yeah, that's interesting, let's find out," and then eventually the guy who was responsible for this did the whole inventory and said, "I'm sorry we couldn't find your film."[2015] Hide

[on Summer in the City (1971)] The hero's path is an escape route, driven by the hope to find a way Show more

[on Summer in the City (1971)] The hero's path is an escape route, driven by the hope to find a way back to himself through the mere movement of travel. Hide

It is very hard to stay inside the boundaries of a genre film; I admire people that are able to do t Show more

It is very hard to stay inside the boundaries of a genre film; I admire people that are able to do that. I just don't have the discipline. What I like about genres is that you can play with expectations and that there are certain rules that you can either obey or work against. But genres are a funny thing. They're heaven and they're hell. They help you to channel your ideas and they are helpful to guide the audience, but they don't help you in what you want to transport other than the genre itself. Genres get angry if you want to tell other stories -- because they are sort of self-sufficient. They like to be the foreground. Hide

I believe very much in overseeable budgets. I really believe in films where the money allows freer e Show more

I believe very much in overseeable budgets. I really believe in films where the money allows freer expression but the budget isn't that big that people are breathing down your neck all the time and looking at what you're doing. The movies that I really enjoy throughout the whole history of Hollywood were never the big pictures; they were the underbelly. Hide

[on road movies] The genre doesn't quite have the same appeal anymore, mainly because everybody trav Show more

[on road movies] The genre doesn't quite have the same appeal anymore, mainly because everybody travels now. Traveling was once a privilege, and being on the road was a state of grace, and not that many people dared to take that liberty. But today, anybody can book a flight to the U.S. and rent a car or bike and go down Route 66 or feel like in Easy Rider ... I made a film in 1990 called Until the End of the World, which was really some sort of ultimate road movie. It was a journey through four continents and a dozen countries. But then it turned into some sort of an "interior journey" into the souls of our central characters. And those journeys into the mind are definitely more dangerous and revealing today ... Hide

Hollywood filmmaking has become more and more about power and control. It's really not about telling Show more

Hollywood filmmaking has become more and more about power and control. It's really not about telling stories. That's just a pretense. But ironically, the fundamental difference between making films in Europe versus America is in how the screenplay is dealt with. From my experiences in Germany and France, the script is something that is constantly scrutinized by the film made from it. Americans are far more practical. For them, the screenplay is a blueprint and it must be adhered to rigidly in fear of the whole house falling down. In a sense, all of the creative energy goes into the screenplay so one could say that the film already exists before the film even begins shooting. You lose spontaneity. But in Germany and France, I think that filmmaking is regarded as an adventure in itself. Hide

I was very much encouraged by American painters who started to use cameras - Andy Warhol, Stan Brakh Show more

I was very much encouraged by American painters who started to use cameras - Andy Warhol, Stan Brakhage. These were painters I liked and all of a sudden they're all making movies. And I started to think that cameras were a logical next step for painters to hold on to. So I started to make little short films, but looked at them as painterly things. I didn't think of myself as a filmmaker; I made these movies as a painter....All of a sudden, I realized filmmaking was something else than painting, and filmmaking used montages and sounds and dialogue and music. And slowly my totally non-narrative films became more and more narrative. Slowly but surely, I turned from a painter to a storyteller.[2015] Hide

[on employing 3-D to film the choreography of Pina Bausch] The body is such an important thing in [h Show more

[on employing 3-D to film the choreography of Pina Bausch] The body is such an important thing in [her] work, and it is fiction on the regular screen. In 3-D, the body has volume. The body is an instrument to discover and conquer space. Everybody thinks that depth is the great thing about 3-D. But in my book, volume is the great thing. Hide

[on the changes in the film industry since the 70s] It's a different ballgame. In the 70s, there was Show more

[on the changes in the film industry since the 70s] It's a different ballgame. In the 70s, there was only one kind of film production. You had a choice to make a film on 35, on 16, black and white, or color, and that was it. And today you can make movies in many ways. You can make movies much more expensively than we ever dreamt of at the time, and you can make them much more cheaply. Financing and preparing a film is a different ballgame. You can't get a movie made unless you have a really good script. (...) Especially if you're a big name director. You have more leeway if you're a first time director, today. If you have a big name, they really want to look at your script. The idea of making a film without a big script, or without a finished script - and I made a number of films without a single page of a script - is unthinkable today. If I were to go out now and try to make Im Lauf der Zeit (1976) they would kick me out of any office of whatever institution or distributor it is that I would try to get money from. Nobody would be willing to invest money in a film with a director who tells you "we'll write it as we go." (...) Yeah, it's much more of an industry now than it was. At that time, there was more of a notion that filmmaking was part of the arts, a language, a form of expression. And if you said today, Well, I want to make a film where two guys are traveling through Germany and they discover the country, and it's about the state of the cinemas, and all these little towns where there's only one cinema left, and it's dying...they would tell you, well, write a script and come again. But at the time, we could still finance the film and I could shoot it over a long period, 11 weeks. Today films have to be made so much quicker, and you have to prepare them for so much longer. Also in post-production, it takes so much longer. At the time, with linear editing, I'd never spend more than a few months in the editing room. But today with digital cinema, you sit there for a year. And then you work on your sound for another year, or six months. So it's all a slower process. Financing a film takes much longer. And very often they tell you, Well, it sounds promising, but we think you need to fiddle around with the script a little more - come back again. (...) I've made more documentaries over the last decade than ever before, mainly because there was so much more freedom in that field, and people could accept that maybe you'd just write a short treatment and not a script. Even in the field of documentaries, I tell you, my students who go out and make their first feature films, they expect to do a documentary based on a script - believe it or not. So it gets a little out of hand. People want more security. They want to know before they make a film what it's going to be like. I was very privileged to start in the 70s, and really make a film a year for 10 years. The only living person who's still doing that is Woody Allen. He has a machinery going; writing in the winter, prepping in the spring, shooting in the summer, editing in the fall. He has it down. But he's the only living person who's still doing that. (...) I was only able to do that in the 70s. In the 80s, it already got more complicated. Every Thing Will Be Fine (2015) took 5 years and The Salt of the Earth (2014) took three years. From the beginning, to the conception, until it's out. So it takes longer, it's more complicated, people need more security, and it's much more of an industrial process. (...) When I started out, it was all based much more on friendship and solidarity. German cinema was strictly possible through an act of historically unmatched solidarity of 15 or 20 filmmakers who helped each other, because none of us would've been able to produce, let alone distribute a movie alone. Even if we didn't like each other's movies, we helped each other. Today, that's pretty unthinkable. It's much more competitive. Films are so much more under the duress of stress. From the beginning, you have a little window, and if the film doesn't click with your audience, it's gone away. A film like Der Himmel über Berlin (1987) if it came out today, would not have a chance. It would disappear. Even at the time, it needed time. It eventually became a classic, if I may say so, but it needed time. Films go through this narrow hole of distribution today and become cult movies or classics...for every one of them that makes it today, I know 10 others that don't. There's so many good movies that do not make it. So I feel privileged I was able to start in the 70s. There was more patience, and a young filmmaker like myself could make a few rotten tomatoes without my career going down the drain. Today it's very difficult to make a second movie if your first one didn't make it. (...) Movies are made with a whole different means today, and when I started out I don't think the word "video" was in the dictionary. Let alone the word "digital." Some computer freaks probably knew the word digital, but we didn't know it was going to change our lives so drastically. [2015] Hide

For an American audience, it might sound totally weird when I say I love it [3D] for its intimacy an Show more

For an American audience, it might sound totally weird when I say I love it [3D] for its intimacy and for the way it brings us closer to people. My colleagues in America connect 3D with effects, loud stuff, and action. I think its real propensity is intimacy and warmth and immersion. It's a fantastic tool to discover the world and tell stories of reality, and it's used for the sheer opposite - it's driving me crazy. I'm very scared that 3D will disappear because people are fed up with it, and think it's baloney, and it's not for them. I'm scared 3D will disappear without ever having been discovered. Even with my new film Every Thing Will Be Fine (2015) people are skeptical. They say, We don't like 3D. Then I try to tell them what it's about, and why I like it, and they're still skeptical, because they've been burned. I am a big defender of the idea that 3D can do things nobody knows about. [2015] Hide

I think the artistic process is one of the great adventures left in our modern times. There are very Show more

I think the artistic process is one of the great adventures left in our modern times. There are very few adventures left to be done by traveling anywhere because everyone has already been everywhere, but creation is still a great adventure. Hide

[on what did he learn from Sebastião Salgado] There's no one concrete thing that I learned from him Show more

[on what did he learn from Sebastião Salgado] There's no one concrete thing that I learned from him, but still there were a number of enormous lessons. To be so radical, and once you've made a realization, draw your conclusions and then change your life, that was something amazing. This man had a great career as an economist ahead of him, and then realized he had a gift for photography and completely changed his life and started from scratch. I don't think many people do that today. And then 30 years later, he gave up that photography because he realized he couldn't handle it anymore. He put his camera down and said, 'That was the last picture I've taken. I can't do it anymore.' That too is radical. Hide

Films can heal! Not the world, of course, but our vision of it, and that's already enough.

Films can heal! Not the world, of course, but our vision of it, and that's already enough.

In the beginning I just wanted to make movies, but with the passage of time the journey itself was n Show more

In the beginning I just wanted to make movies, but with the passage of time the journey itself was no longer the goal, but what you find at the end. Now, I make films to discover something I didn't know, very much like a detective. Hide

Originality now is rare in the cinema and it isn't worth striving for because most work that does th Show more

Originality now is rare in the cinema and it isn't worth striving for because most work that does this is egocentric and pretentious. What is most enjoyable about the cinema is simply working with a language that is classical in the sense that the image is understood by everyone. I'm not at all interested in innovating film language, making it more aesthetic. I love film history, and you're better off learning from those who proceeded you. Hide

Sex and violence was never really my cup of tea; I was always more into sax and violins.

Sex and violence was never really my cup of tea; I was always more into sax and violins.

There's a film of John Ford called The Searchers (1956) and sometimes I think that's [my] main topic Show more

There's a film of John Ford called The Searchers (1956) and sometimes I think that's [my] main topic. ... It's searchers. It's people who are searching, trying to define what they live for, trying to find [the] meaning of their lives, trying to find their role in life, looking for love, searching searching searching. That seems to be the key thing my characters are doing.[2015] Hide

I will always produce my own films and avoid finding myself at the distributor's mercy. You must bec Show more

I will always produce my own films and avoid finding myself at the distributor's mercy. You must become a producer if you want any control over the fate of your work. Otherwise, it becomes another person's film and he does with it what he pleases. I only had one experience like that and I will never repeat it. Hide

My first impressions of beauty [were] not in life but strictly in paintings because I was born right Show more

My first impressions of beauty [were] not in life but strictly in paintings because I was born right after the war. My hometown of Düsseldorf was flattened, 90 percent of the city was in ruins, and as a kid that's what you take for granted. That's what the world looks like. But there was a better world and that was all these cheap art prints my parents had on their walls. And there were some old Dutch paintings and French landscapes ... and these cheap prints gave me the idea that there was a different kind of world out there.[2015] Hide

Wim Wenders's FILMOGRAPHY

All

as Actor (18)

as Director (7)

as Creator (6)

![The Salt of the Earth [Sub: Eng]](https://static.new-movies123.link/dist/img/YRaALydQyz8C1L9iV2Mb2TQRH_sL-9EtXyW11xLLEDtJ7mtsoH1nRktR7HnMdKCB2fPfsUNeM2LReWutj2O_RCVSRZp6Bii-AeKUkTsVV8mHx4ulZjntbY2piUlMwD2O.jpg)

![Wings of Desire [Sub: Eng]](https://static.new-movies123.link/dist/img/UfwsXQqV8iZF1-S5qhmnkq55ed37xnI2BY9A2e0MZLFgQXQNKdRp3kBCPOnB_kSJy_6EEh-1yV4xafWEq8kiUuMYvV6xbNkAOz5VxeEmgJ4.jpg)

![Acqua e zucchero: Carlo Di Palma, i colori della vita [Audio: Italian]](https://static.new-movies123.link/dist/img/R6K7vKPGi8eQzZLdPQ9eXi0greyTRKo9xgC8cpMSTR0lSkLqm4n27BMlyTppvTu4KHfiYIavv2P8znoCSV3braTvDuwJp5NhWnGqVothuXl5r-CPPp2r9Ga9auyJmKCX.jpg)

![Buena Vista Social Club: Adios [Audio: Spanish]](https://static.new-movies123.link/dist/img/6LbxpwLLHpBtOT8mM_QNgyn2QvalJENQ_LdjFpNqQ7HYZ6bxuONJfTaQ2qGjVcjwPOcwnDi41pH7ZI4rf-HYn4ujip-GTW-G3GS4RuyQ5rdYBrT5Gd4JlnP20zQS7aC8.jpg)